To see the previous installments, click on the following links: #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #7, #8, #9, #10, #11, #12, #13, #14, #15, #16, #17, #18, #19, #20, #21

The fate of Marcus's son, if found guilty by Vespasian, would be sealed under the weight of the severe Roman imperial justice, implacable in its mission to maintain the order and authority of the ruling family. The trial would be brief, as it is when the interests of the highest hierarchy are at stake. The accusation, driven by the influence of the gens Flavia, would leave no room for leniency or excuses. The crime of having murdered the son of a family so close to power was an unforgivable act, even if the mental fragility of the accused was acknowledged.

The process of execution, in such a case, would follow the Roman tradition reserved for those who had seriously offended the res publica or the emperor himself. Depending on Vespasian's judgement, the son of Marcus could face a number of possibilities, all of them cruel, designed to exemplify the punishment and deter others. Among these, the most dreaded would be the death sentence by damnatio ad bestias, the execution in the amphitheatre, where Marcus's son would be thrown to the wild beasts in front of a crowd clamouring for spectacle. This public and humiliating execution not only sealed the fate of the condemned man, but also reminded the people that imperial justice was absolute and implacable.

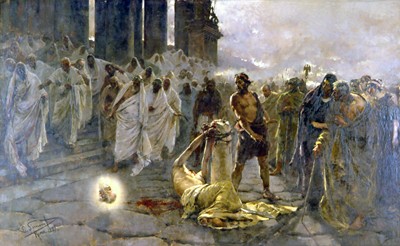

Another possibility would be execution by decapitation (ferrum), which would be quicker but no less symbolic. He would be taken to the place of his death, bound and guarded by the lictors, the executors of the state's will, who would lead him to the scaffold. There, surrounded by his executioners, the son of Marcus would kneel, his arms bound so that he could not resist the final blow. The sword, sharp and ready, would fall on his neck, severing life from his body in a cold and final instant. Decapitation was considered a less brutal method than others, but equally irreversible.

Executions in Rome were always accompanied by a protocol of solemn silence, and the air was filled with heavy expectation. The very wind seemed to be suspended in time as the act unfolded, as if even the gods waited on high to witness man's punishment before the imperishable laws.

If Vespasian, aged but still feared, felt that the death of Marcus's son was necessary to restore the honour of the gens Flavia, there was no hope. Only divine judgement before the gods of the underworld would await him.

To be continued

Header Image:

Beheading of Saint Paul by Enrique Simonet y Lombardo. Museum of Malaga (Spain)

Oh, my goodness......I didn’t know that Roman executions were so brutal.

Yes, Yumi ( @yumiyumayume ). It was brutal and exemplary. These types of executions were for free men or Roman citizens. The slaves had it much worse...they were crucified and died, generally, by axphysia and with terrible pains....

The cruel part was upper class people entertained watching the brutal scenes. Chinese executions were also brutal.

Such was the death suffered by our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ for the sake of our sins. People criticized Mel Gibson for his brutal portrayal of the Crucifixion, while others say he didn't do it justice.

Yes, Uly. Jesus was crucified because he was considered a serious political threat to Rome. He was crucified on the charge of proclaiming himself ‘King of the Jews,’ which the Roman authorities interpreted as a rebellion against the rule of Rome and Caesar.

It is known that crucifixion in Roman times was a punishment reserved primarily for slaves, prisoners of war and low-level criminals.

Mel Gibson's crucifixion was impressive in its realism.

And He proclaimed himself equal to God, which flew in the face of Jewish law, so he was doubly condemned. I think Mel Gibson's Crucifixion is hard to watch but good to remember.

I totally agree with you, Uly