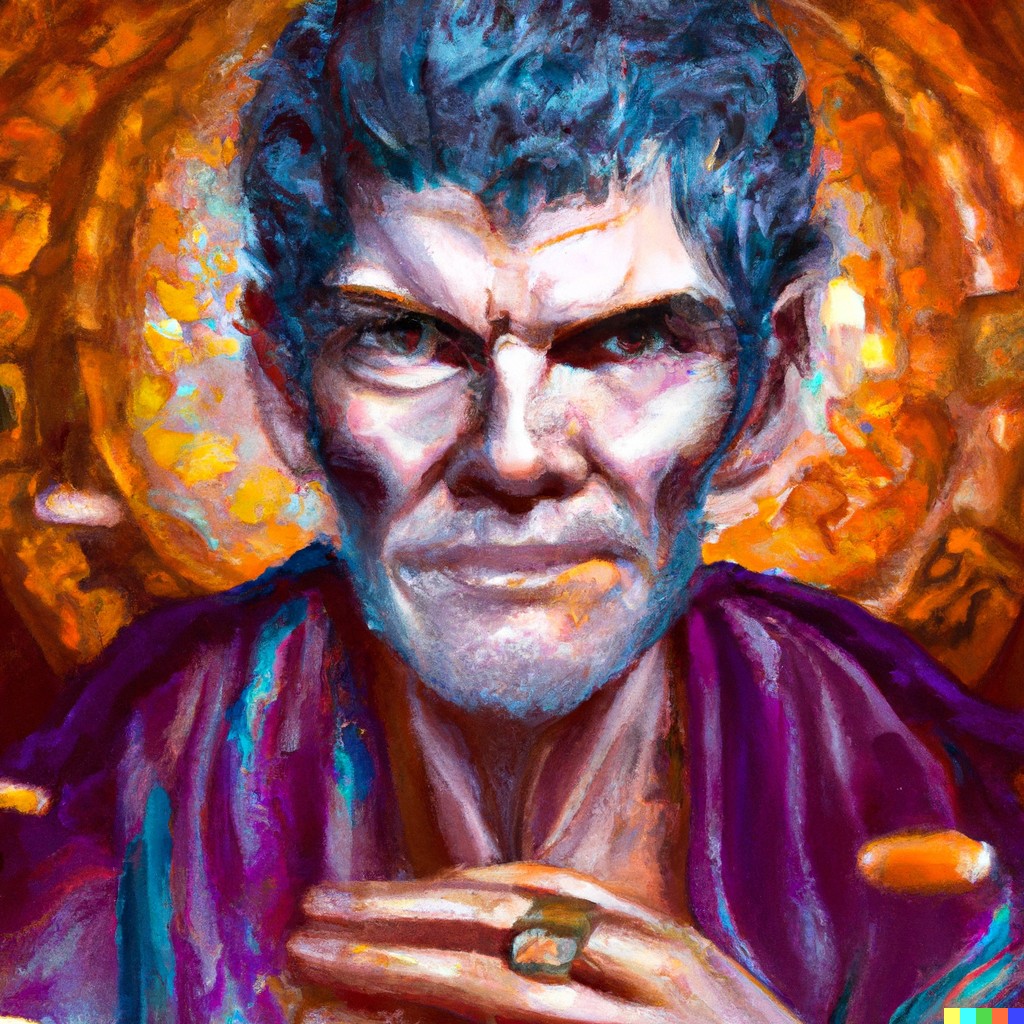

A book written almost 2000 years ago starts with a reflection on how we use our time and encourages us to make the most of every hour, in order to be truly ourselves. An inattentive life and time spent in a careless way is the biggest waste, says Seneca. The text startles me thus as unbelievably modern – wasn't it modernity that was supposed to be obsessed with time and efficiency? And yet here is the voice of an author who would never imagine a mechanical clock, an accurate map of the world, or a railway station, but doesn't need these inventions to be able to grasp the underlying drive: the need to take control and the striving to eliminate unspecified moments and unspecified spaces.

Seneca was deliberate in his aspiration for everlasting influence. Instead of writing a dialogue, a treatise, or a speech, which were common forms for ancient philosophers, he chose to put his teachings in the form of letters to a friend. His recipient, Lucilius, seems to be a real-life friend of the author and a young follower of stoicism. Throughout the letters, we discover new details about the life of Lucilius, and the relationship between the two men becomes more palpable. In this way, the text stays vibrant and philosophical considerations never steer far away from the realities of life.

In the very first sentence of the first letter, Seneca exhorts his friend to take control of his time, which is supposed to be the same as reclaiming authority over his own life:

'Do that, dear Lucilius: assert your own freedom. Gather and guard the time that until now was being taken from you, or was stolen from you, or that slipped away.'

The translation I'm reading is quite free and very modern*. There seem to be neither civilizational nor intellectual barriers between Seneca and me. It's easy to start reading and the topics covered by the particular letters could as well be titles of episodes of a self-help podcast on Spotify: 'Taking Charge of Your Time' (the first letter), 'A Beneficial Reading Programme' (2), 'Trusting One's Friends'(3), 'Avoiding the Crowd'(7), 'Anxieties About the Future'(13), 'Safety in a Dangerous World' (14), 'Saving for Retirement' (17)...

The first sentence in Latin: Ita fac, mi Lucili: vindica te tibi literally translates to: Do that, dear Lucilius: reclaim yourself for yourself. The time we have during our life is actually the only possession that is truly ours; nothing else belongs to us completely. But instead of treasuring time, we are big, careless spenders.

If we continue this train of thought, we could even say we are our time. We are alive for only as long as we have time left. The next opportunity when you give someone some of your time, think of it as giving them some of your life: you will feel more like a Stoic.

There's a modern saying: time is money. I realize now how deceitful that can be. Time is not money; time is you and you cannot buy yourself back. No amount of money will change the fact that every day is a day when we are dying, for 'all our past life is in the grip of death'.

Stoicism seems so radical in its endeavor, so uncompromising. 'While you delay, life speeds on by'. It's also an ancient anticipation of the threat of procrastination and an attempt to avert it: 'If you lay hands on today, you will find you are less dependent on tomorrow'.

And yet, and yet... are we really vindicating ourselves when we exert absolute control over our time? What about daydreaming, walking without a purpose, waiting for a bus when you don't know the schedule, waiting out a storm or an overwhelming feeling, sitting with someone in silence, sitting with yourself in silence, trying to suppress your thoughts? I suppose a Stoic would say that those are not meaningful moments of my existence, but I'm not convinced. As much as I value rationality, I'm reluctant to think that perfect rationality is desirable in itself. But I'm not sure why.

*Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Letters on Ethics, translated by Margaret Graver and A. A. Long, University of Chicago Press, 2015.

There might be a few errors here and there, but this post is super well written not just in mechanics but also in content and organization. You discussed complex ideas while tapping into the English language mindset.

Unfourtunately, I don't know appropriate words in English to express the storm in my mind after this reading. The beauty of ideas and sentences is the same attractive thing like a physical one. I'd like to discuss this topic further and deeper... if I could.

Thank you so much JG and Alex ☺️

Bravissima! As Machiavelli would say History repeats itself and People don't learn from their mistakes, thus they keep making the same mistakes over and over again.

By that I mean that we shouldn't really be surprised by how "modern" certain ancient philosophers may sound.

As for the concept of time, I can't say much there. The metrics whereby we measure our time tell us how we're spending our life.

I've read a bit about stoicism. You are right. My intentional part of mindset is quite close to many maxima of ancient stoicism. Unfortunately, my behaviour doesn’t reflect my intentions or willings in reality. Being a firm stoic is not so easy…

So, let’s discuss our different views on Life!

@Simone thank you! I'm often surprised by how easy it is to read ancient texts, but I suppose it has a lot to do with the translation. I suspect that in what is seemingly similar there have to be hidden substantial differences due to the multiple thresholds of epochs between us and them. @Alex I hope you'll never become a real stoic, stoics are boring ;D I think there's something wrong with stoicism (and I'm going to explore it further), although I understand their appeal: they promise you control over your emotions.

@Lokus I agree with you. To fully understand ancient philosophers, we should first have a profound knowledge of the period in which they lived. Otherwise, we're decontextualising. Context is as important in language learning as it is in anything else😅.