History will always repeat itself; every event that occurred in the past will reemerge in the future, either in the same pattern or in a different form, depending on the conditions of the time.

The beginning humans lived in small, egalitarian groups based on consensus. This became the earliest foundation of the organization, where all decisions were made with the primary goal of survival. Around 4000–2000 BCE, the emergence of agricultural practices led to the need for hierarchy, giving rise to more organized structures of power.

Mesopotamia, with its centralized governance, the Roman Empire, with its republican–imperial political organization, and European feudalism, with its aristocratic networks built for military and local authority, all represent early patterns of organizational formation aimed at achieving specific goals. Naturally, the practice of gathering and organizing carried different motives in each era. Many relied on ideology as a unifying force, such as the Church and other religious groups that built political legitimacy well into the modern era, which history books record as Gospel. Others took the form of voluntary associations like guilds, which became important social structures before the modern era in both economics and politics, driven by motives of wealth, what we call Gold, as well as organizations built in the name of the people’s honor and identity, structured to form kingdoms and accumulate power, which we refer to as Glory.

From the 19th century to the modern era, we again witness how organizations transformed from rigid, monarchy-inspired structures into more dynamic social systems, increasingly connected to their surrounding social environments. Today, organizations form far more easily, beginning with individuals overwhelmed by heavy tasks who then delegate responsibilities to others, or study groups in schools collaborating to complete major assignments together.

Initiation to collaboration often evolves, as there is always the potential to pursue larger goals in the future, such as subsequent projects or even the establishment of a shared crypto academy built upon long-standing trust and familiarity.

In the technological era, organizations are gradually evolving into forms we may not even consciously perceive, shifting toward structures based purely on shared objectives. These goals are achieved collectively with like-minded individuals, as seen in blockchain-governed communities, a decentralized ledger system for tracking digital assets where decision-making is carried out through governance tokens, granting voting power proportional to token ownership.

The concepts of crypto-anarchy and network states demonstrate how digital communities can grow into powerful political entities without requiring physical structures like traditional organizations. Bitcoin, which has no nation-state, headquarters, or formal organizational structure, is capable of managing monetary value worth trillions of dollars, influencing national monetary policies, and enabling cross-border transactions without intermediary fees. Its rules are determined by code rather than state laws or central banks, and its decision-making processes are safeguarded by miners and nodes rather than institutions—liberating it from centralized authority.

The war between Russia and Ukraine further illustrates how such communities can function as tools to raise hundreds of millions of USD to fund warfare, significantly influencing geopolitical conflict. Digital, stateless money allows actors behind it to bypass international banks and even United Nations regulations, transforming it into a powerful, structured instrument of power, reinforced by strong data security for its users.

Data security, transaction speed, and immense value have thus become defining patterns of modern organizations in their pursuit of Gold, Glory, and Gospel.

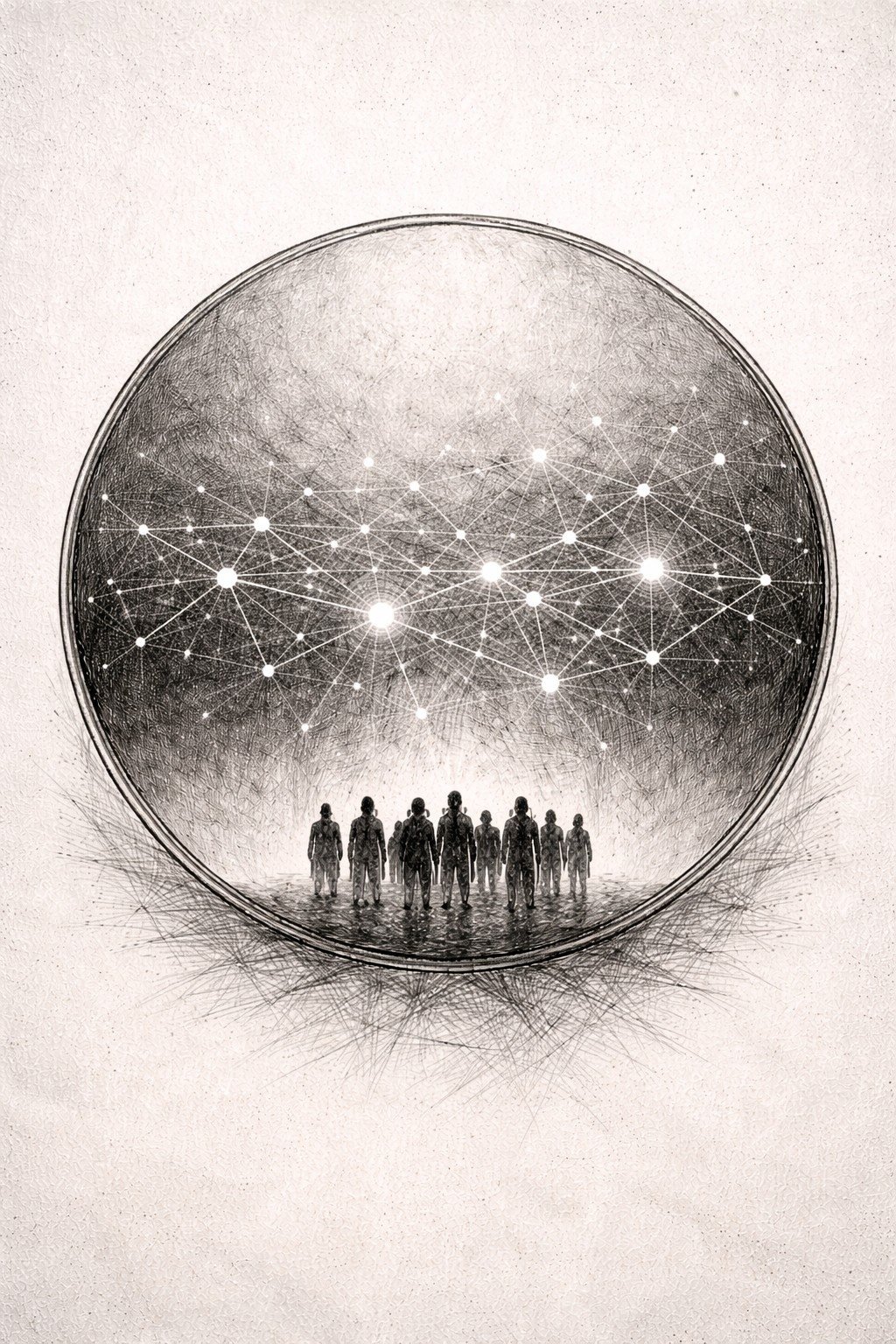

Ultimately, organizations are not static entities but reflections of human needs in their respective eras. From egalitarian consensus-based groups, agrarian hierarchies, imperial power, and religious ideological legitimacy to digital networks built upon code and cryptographic trust, one consistent pattern emerges: humans will always seek ways to gather, self-organize, and pursue shared objectives.

Technology does not eliminate the essence of organization; it merely transforms its form and medium. Where power was once legitimized by bloodlines, land, and doctrine, it is now increasingly shaped by algorithms, networks, and borderless collective participation. Blockchain, DAOs, and digital communities are simply the latest manifestations of humanity’s ancient drive to assert sovereignty over resources, values, and its own future.

History may repeat itself, but it is never exactly the same. It adapts to new contexts, tools, and challenges. In an increasingly decentralized world, modern organizations no longer need to be visible, possess offices, or receive state recognition to wield power. Shared goals, trust, and transparent systems are sufficient for a community to form tangible influence. Thus, Gold, Glory, and Gospel have never truly disappeared—they have merely found new vessels. And like previous cycles of history, today’s organizational forms will become the foundation for future social and political structures, whether we realize it or not.